Showing all 2 results

-

Nobody Loves Me

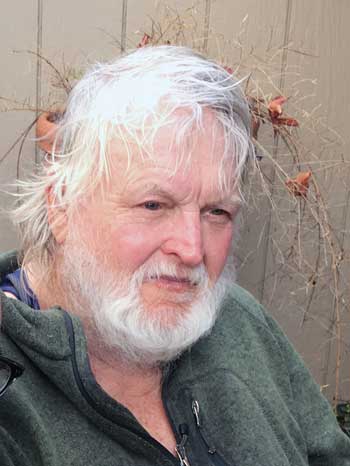

$9.99 – $32.95John Stoss

9781944884987

More than 50 years of work from a unique American voice.

John Stoss was born in Great Bend, Kansas on April 17, 1940 and grew up in and around the communities of Olmitz and Otis, Kansas. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas. He entered the Master of Fine Arts in creative writing at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, where he met C.D. Wright and Frank Stanford, among may other poets. In 1977 Stanford and Wright published John’s first book, Finding the Broom, the second book to be published under their legendary Lost Roads imprint. This began a writing career which now spans half a century. John’s other books include Machines Always Existed (Portals Press, 1984) and Whatever Passes for Love is Love (Lavender Ink, 2012), along with Nobody Loves Me: Collected Poems of John Stoss (Lavender Ink, 2020). Among these works are countless others: paintings, plays, poems, screenplays, and songs John shares with family and his many longtime friends. John lives in Salinas, California. His definitive biography is the poem, “The History of John Stoss,” by Frank Stanford, collected in Stanford’s book You (Lost Roads, 1979) and also in The American Poetry Review (1979). See too his autobiographical poem, Nobody Loves Me, in the Collected Poems.

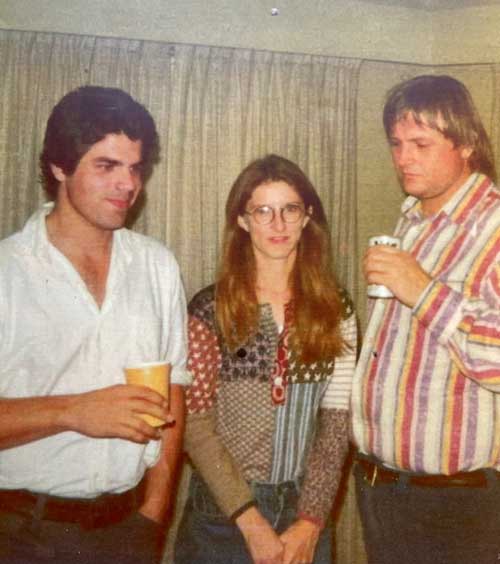

Alan Dugan came to the University of Arkansas to read in 1969. Frank Stanford, then a student, met him there and had some correspondence.

In some ways John Stoss (not only his writing) is a legacy of the Beats, the first group of writers that spoke to him, but with a strong current of the 60s radicalism that followed, and the continual search for authenticity, though in John’s case, authenticity was/is his entire being, no search required. (No drugs required either, and just a second beer could make him woozy, despite his size.) He still projects the vibe of a farm boy who can’t quite get accustomed to the sophistications of the city.

Before I met him in 1970, John Stoss was already the stuff of legend; in my case, the legend was imparted by Fred McCuistion, himself a legendary story teller (strictly oral tradition) in Fayetteville, Arkansas. I recall Fred’s evocation of the image of a beached whale, also his suggestion that the sound of ‘the rending of metal’ described something about John’s relation to the world.

But the Stoss I met just seemed like a simple soul with a raucous belly laugh and a love of walking. We became acquainted first, and friends ultimately, on long walks around Fayetteville that often took us way out into the countryside. At the time, we were both enrolled as students in the University of Arkansas MFA program, which John would eventually abandon as too restrictive and essentially irrelevant. He stayed in town anyway, reading and writing at a breakneck pace – the first among us to discover One Hundred Years of Solitude, or to find the brilliant flame in the quiet poems of ancient China, always searching, always full of energy, enthusiasm, always kind and invariably helpful with everyone.

We shared a house during one of my four years there, along with the late, great poet Leon Stokesbury and – for a while – Neal Spearmon, a handsome, troubled physics major whose suicide is mythologized in one of Frank Stanford’s poems, as is Stoss himself. I had a tiny upstairs room adjacent to Leon’s; John’s room was next to the front door. I’d see him often when I was coming or going, sitting at his typewriter, gleefully turning out pages of a long, never published novel, called Little Brothers. John had a habit of rubbing his hands together and letting out a whooping laugh when he had written something he especially liked. The pages piled up all around him, and when he got to the end of the novel, he wrote it over again, from scratch. His work ethic was staggering to see, then and now.

John has almost never (I can think of one exception, a brief one) held a conventional job, surviving on astonishingly small amounts of money, but he never, ever was idle. In this book we see some of what he wrote a long time ago in the poems from Finding the Broom, and what he has written just very recently in the long autobiographical poem. Along the way, he has written several other novels (one of them published in the early ‘80s, called Machines Always Existed), created hundreds, maybe thousands of paintings, some on canvas, many on cardboard or whatever material was handy. (Often these are scenes from the farm, or other landscapes that impressed him like New Orleans’ Jazz Festival. While the style is ‘primitive,’ it is not naïve, and often the paintings are breathtaking in their insights, especially the portraits.) Stoss also tried his hand at film-making, creating at least one feature length film in Super 8, himself playing the main character, Honey the Hobo. (The film, in its partially completed form, was thrown into the Mississippi River by a woman he was staying with in New Orleans who had grown impatient with John. A few outtakes remain, which I have in a coffee can, in the same way I seem to have the only extant copy of Little Brothers.)

As bad as he has always been at self-promotion, you could say he has been even worse at self-preservation, or at least of preserving the art he has produced. Though there have been a number of shows of his paintings, mostly arranged by friends, he has few if any in his own possession; for a long time, the paintings not sold or given away were kept by photographer Debbie Luster, who collaborated on several projects with C.D. Wright, and was the closest John ever came to having a patron. As she has moved to another country, those paintings are also now in my house.

John has written many songs, and has even sung them in some public performances, and on a CD produced by musical collaborators. He also wrote an unclassifiable play-screenplay type of thing, published by Lavender Ink, called What Passes for Love Is Love. Typical of John, his intention with this strange and compelling piece of theater (based on his time in The Maple Leaf Bar during an imaginary hurricane) was to give his friends a vehicle with which to enter the lucrative world of film-making. That it is a remarkable piece of writing that is unlikely to ever be produced simply reconfirms John’s status as a generous friend and an undiscoverable genius.

There are many stories; everyone who has known John has ten or a thousand, often involving the disastrous state of his wardrobe, or the occasionally terrible results of his cooking (like the fish-head soup he made for a party in New Orleans), though in truth, Stoss’s essentially Spartan diet of fruit and vegetables probably accounts in part for his vigorous longevity. The stories are not always kind, but they are invariably affectionate; John is beloved in any of the places he has called home, despite the title of his autobiography. The best of the stories is probably the one writer Lewis ‘Buddy’ Nordan published in The Atlantic, a thinly fictionalized account of Stoss (Tom Cloff) traveling through the winter landscape with a typewriter and parts of a pig, coming to stay with Buddy in Fayetteville; the essence of Nordan’s story is to present his character, Stoss/Cloff as the perfect guest. While not everyone would agree, John is at the very least always a memorable guest. Once when he stayed with me a few days in New Orleans, he’d return home in the evening with the day’s catch from dumpster diving (often big bags of Popeyes’ fried chicken) and tales of the various homeless people who lived in my neighborhood, as well as the skinny on proprietary sensitivities about the area’s various dumpsters.

John has not adapted well to new technology. Though he has a phone, he doesn’t text or even email, is not on any social media platform, and often writes in longhand. His letters arrive frequently folded up with the address scribbled on the outside of the letter itself and the stamp affixed there. It’s more economical that way – he doesn’t have to buy an envelope.

John has lived in California for several decades now, first in the Carmel area, one of the most beautiful locations on earth, where he parked his car, more recently in Salinas, where one of his literary heroes, John Steinbeck started out. In the 70s, he lived in Fayetteville, and then back and forth between there, New Orleans, back home in Kansas, and maybe other places. The Kansas/farm influence can’t be overstated, as little as farm labor suited him, nor did the landscape, which he described as like ‘living on a cold pancake.’ He sometimes traveled Beat-style in the 60s and 70s, as well, and took at least one cross-country journey on a flatbed train car, his back against the giant wheel of a truck being transported across the northern states, in the dead of winter. As much as he may have wanted to make New Orleans home, the climate always thwarted him, causing a bad cough. One of several times he left for good, he pronounced it ‘a city of the dead,’ though living in his car alongside Audubon Park, with the radio tuned to jazz and a bag of wilting vegetables beside him, he could look comfortably at home.

I appreciate the opportunity to write this introduction, and the work that Justin Chimka put in to organize and ready the recent work for publication. Bill Lavender’s and Lavender Ink’s visionary relationship to the project will be noted and celebrated over time, I am certain. There is no one like John Stoss, the person or the writer, besides that humble, often jolly, dog-loving, possibly disheveled genius who writes and creates as naturally as most of us breathe. His friendship has been one of the great gifts of my life. I believe those of you reading his work here will feel a kinship that you will have difficulty defining, an affinity that will remain part of your life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.