Showing all 4 results

-

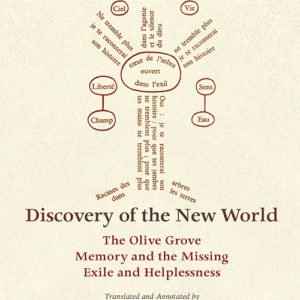

Discovery of the New World

$9.99 – $29.95Nabile Farès

Trans Peter Thompson

9781944884901

First appearance in English of Nabile Farès’ great trilogy, La Découverte du nouveau monde. -

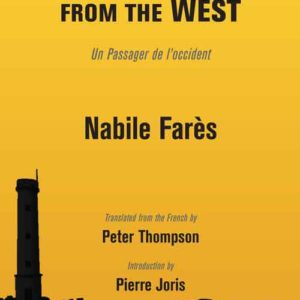

A Passenger from the West

$9.99 – $16.95Nabile Farès

Trans. Peter Thompson

Intro by Pierre Joris

With James Baldwin interview

9781944884451

Nabile Farès was a Kabyle, a Berber, and one who spoke Berber before he spoke Arabic or French—one who wrote throughout his life about Kabylia and its Berber stronghold. In fact his doctoral thesis centered on the figure of the Ogress in Berber folklore. It is worth noting that Kabylia is one part of Algeria never fully subdued by Arab or French invaders.

Nabile Farès was a Kabyle, a Berber, and one who spoke Berber before he spoke Arabic or French—one who wrote throughout his life about Kabylia and its Berber stronghold. In fact his doctoral thesis centered on the figure of the Ogress in Berber folklore. It is worth noting that Kabylia is one part of Algeria never fully subdued by Arab or French invaders.

You must be logged in to post a comment.