Description

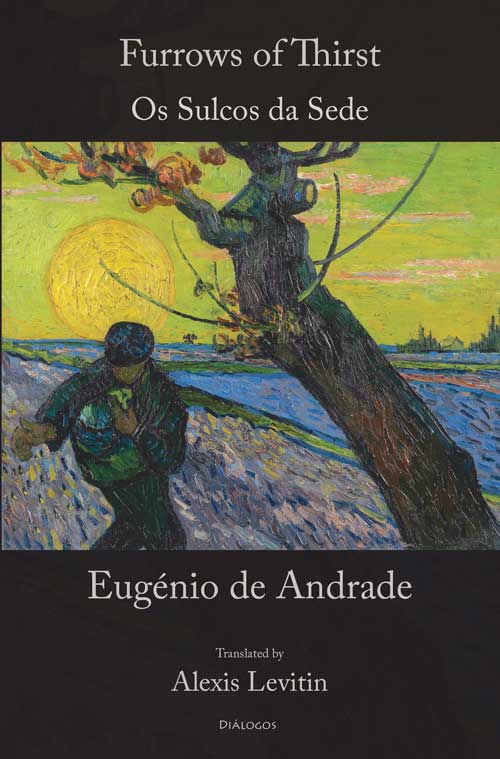

Eugénio de Andrade

Translated by Alexis Levitin

Furrows of Thirst

(Os Sulcos da Sede)

ISBN: 978-1-956921-09-0 (pbk.)

(May, 2023)

Pushcart Prize Winner, 2023!

“A poetry of the body, a body with the potential of light, continually purified, that seeks out the word as a means of ascension.”

—José Saramago (Nobel Prize for Literature, 1998)

“Levitin gives us the brilliance of de Andrade’s poetry in rich and musical language. We owe him a debt for illuminating the work of this superb contemporary poet.”

—Colette Inez

“The little country that is Portugal turns out great big poets like Camões, Pessoa, and more recently Eugénio de Andrade. … Alexis Levitin’s versions are right to that exact point. Enjoy!”

—Gregory Rabassa

“For all his gentleness, his civility, it is a fierce solitary who speaks in these verses, a man on whom the terrible insistences of Rimbaud and Verlaine… have not been lost.”

—Richard Howard

Through the simplest and most elemental images, in a tone of melancholy wonder, Andrade’s last poems resonate with the mysterious silence of impending oblivion. Snow and fire, winter and summer, thirst and relief coexist in a dialectical dance of immediacy and memory whose rhythms are gracefully echoed in the subtle lyricism of Alexis Levitin’s translation.

—Stephen Kessler, translator of Desolation of the Chimera: Last Poems by Luis Cernuda

Preface by Alexis Levitin

Eugénio de Andrade was Portugal’s most popular poet at the time of his death in 2005. In the course of his career, he won all of his country’s poetry awards, including the prestigious Camões Prize, as well as The European Prize for Poetry and France’s Prix Jean Malrieu. Here in the United States, he is represented by eleven collections of finely-wrought verse, including Forbidden Words: Selected Poetry of Eugénio de Andrade from New Directions.

Eugénio’s craft is to sing the Portuguese language with the simplicity of a bird. His triumph is like that of a great athlete: he makes it look easy. He makes it look natural. But the delicacy, precision, and beauty of his poetry is, like all great art, achieved through what he calls, borrowing from Leonardo da Vinci, ostinato rigore. That stubborn adherence to the musical rigor of words is what sets him apart from other great Portuguese poets of the 20th century. His numerous drafts, revisions, rewritings, re-listenings, are testimony to his religious dedication to the beauty of language. Eugénio was proud to have been referred to as a Pagan poet and it is clear from both his own commentaries and the internal evidence of the poems themselves that music is the yearned-for fulfillment of this man who worshipped the body, the senses, the loveliness of blossoms and the song of birds.

The beauty of his verse, however, is a hard-won victory. He is not an unconscious participant in the weave of nature’s panoply. In fact, he is supremely conscious, supremely aware of the minutia involved in his daily struggle for perfection. In a poem that appears in Labor of Patience, a book written seven years before this one, Eugénio focuses on his eternal search: “All morning I was searching for a syllable” he says, because …. “Only it could shield me from/January cold, the drought/ of summer. A syllable/ A single syllable./ Salvation.” In this collection, which he must have sensed would be his last, the very first poem, “To See Clearly,” refers to “those burning syllables” to which he always returns. The second poem begins with the imperative “Go syllable by syllable” and concludes with the repeated exhortation “Syllable by syllable/walk to the empty/water jug. –Now so full!” In “Winter Poem,” he balances against old age the freshness of words, “a murmur of morning syllables,” though in a later poem he recognizes the almost desperate nature of the poetic impulse, speaking of “hoarse syllables/moist with desire.” Finally, in a “Simple Thought,” he calls those carefully gathered syllables by their rightful name, when he says “It is music….It will stay with you the rest of your days.” Clearly, Eugénio would embrace Walter Pater’s claim that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” In our struggle for meaning, for existence itself, it is clear that Eugénio banks on the music of his language for his salvation.

Though he builds his nest and monument of words and syllables, Eugénio is clearly delighted by the rewards that come to us through our five senses. The poetry, after all, must spring from life and the four elements that sustain it. As he says in a short poem called “The Fruit”:

This is how I want the poem to be:

trembling with light, coarse with earth,

murmuring with waters and with wind.

In this last collection alone, notice the delicate intrusion of the senses. For touch there is “the she-goat/its muzzle moist with dew.” Or “doves trembling in heat” or “a few drops of rain on someone’s hair.” For smell, there is “the scent/of wisteria dripping from the wall” or “a body…that smelled/ of ripe apples”. For sound, as already noted, we have the “murmur of morning syllables” or the sun which “sings as it burns.” For sight we have “trembling furrows in black earth.” And for taste, we have the stunning conclusion of his “Last Song”: “give me thirst itself to drink.”

Eugénio loved the natural world and the senses through which it penetrates to our core. He also loved the élan vital of his own blood and being. Approaching the end, he is not resigned. He speaks of “the cadences of the heart/stubbornly repeating that it’s not grown old.” In another poem he begs “Give me another summer.” In a poem dedicated to Rilke he speaks of “the intimate flame of a fire/that refuses to go out.” But in the end, he ruefully stares reality in the face: “You will leave the house unfinished.” Indeed, we have no other choice.

This book is Eugénio’s last testament. It testifies to his love of life, both around him and within. It testifies to his enduring love of language and of music. The deepest eros of this man, this poet, beyond the desires of the body and the sensuality of nature, springs forth in his lifelong dedication to the sound of words. It is the eternal eros of the music of his song.

—Alexis Levitin

Morrisonville, New York, Summer, 2022

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.